Image credits: Günter Kresser // Katharina Stiglitz // Heidi Holleis

Fantôme Exceptionnel

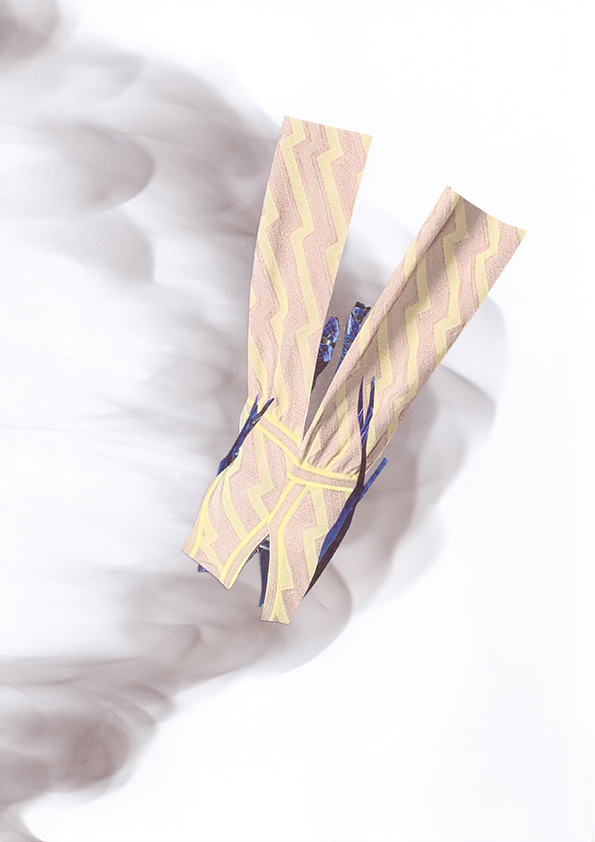

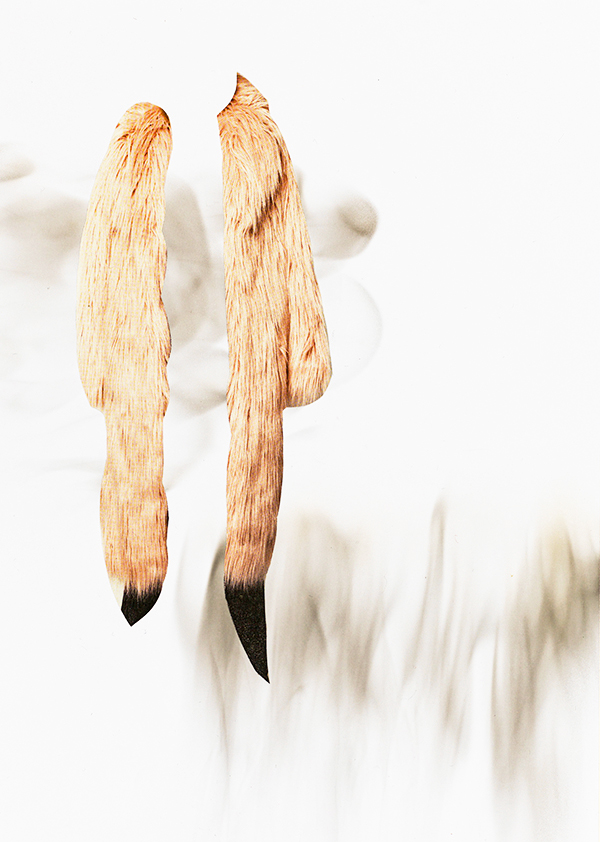

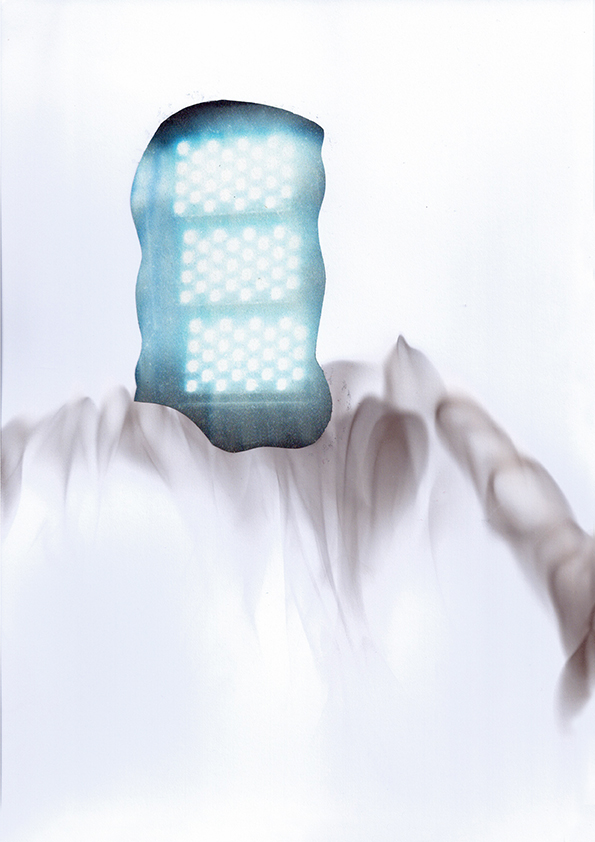

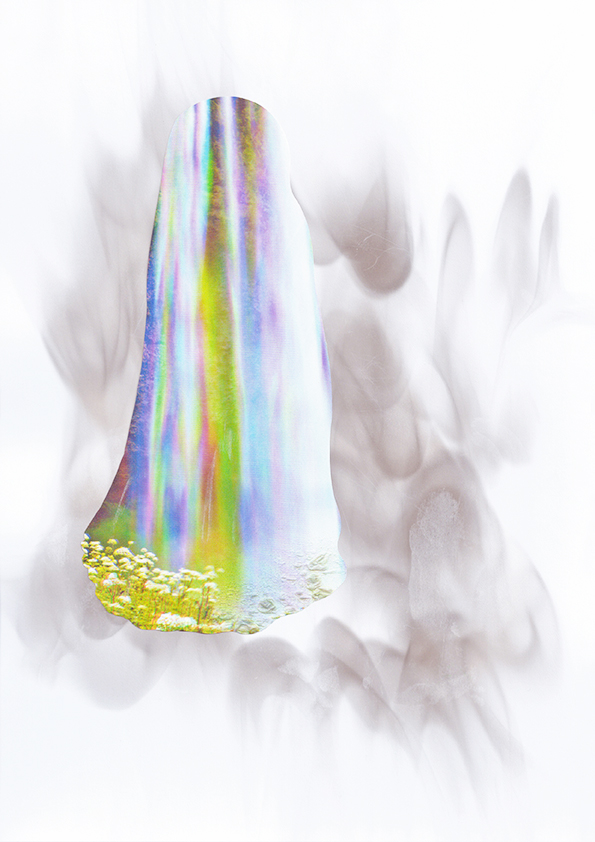

In her work series “Fantôme Exceptionnel”, Holleis explores the ghostliness in connection with the term “Hauntology”. With recourse to Jacques Derrida, the term refers to the presence of ideas and thoughts that we practically inherit from the past and that dictate our presence. This spook of yesterday or such revenant old ideas can be found in Holleis’ works in the form of cut up fashion magazines or web images that, together with the soot of candles, create strangely ephemeral phenomenal worlds.

(Sussudio, translated by Maria Magdalena Larch)

Fantôme Exceptionnel: Hauntology

In her series of works “Fantôme Exceptionnel”, Heidi Holleis refers to the concept of “Hauntology”, which lately popped up especially in the electronic music scene. The term was coined by Jacques Derrida, who, in a way, therewith articulated a cultural diagnosis, which states that Europe is possessed by its ghosts. Theories, ideas and ideologies that seemed to be passé still haunt and shape the European mind-set. Derrida particularly had in mind the theories of Karl Marx that, after the end of the Cold War, were considered to have failed but are still valid and appealing in European thinking today – since the last financial crisis even more. The late Mark Fisher took a broader view of the term, referred it to pop music phenomena and warned against drifting off into a mere nostalgia mode (Fredric Jameson), in which you cannot draw a specific picture of the present anymore due to an excessive nestling into the past. This would mean that history, as a sequence of significant phenomena, or history with a dialectic promise of the future, had an end – and with that, history itself, as it was thought of up till now.

In her small format collages, Heidi Holleis uses vintage-looking photo shoot pictures from fashion and lifestyle magazines, which can be seen as ghosts of the fashion industry, as well as the soot from burning candles, which expresses the ephemeral floating and therefore unboundedness of “Hauntology”. The paintings seem to be light, too light, but their supposed nebulous nothingness becomes heavier the more you look at them. Desubstantialized arrangements, which thus abstract corporality, demand attention with their sheer presence. “Capital is at every level an eerie entity: Conjured out of nothing, capital nevertheless exerts more influence than any allegedly substantial entity.” 1

(René Nuderscher, translated by Maria Magdalena Larch)

Phantom Force

“I am not afraid of ghosts but rather of people who are afraid of ghosts.”

(Heidi Holleis)

Facts become blurred at the limits of language, once clearly recognizable images become blurred. This seems dubious, surreal, unbelievable, maybe even scary. At the limits of language, there are images that, like ghosts from a past that nevertheless bury themselves contemporarily and ordinarily into our present, create themselves through cognitive processes and point out our linguistic and symbolic limits.

The 7th sentence of Wittgenstein’s “Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus”, which entered common parlance long ago, reads as follows: “What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence”. Here, Wittgenstein drew a line; that of language. We could stay silent but can our unconscious affects that constantly cluster new images and, if perceived appropriately, ghostlike structures do the same?

Surrealism – the way of which was paved by Dadaism and which, from one of the countless points of view (again an interpretation of signs), symbolizes a return to the bourgeois love towards mysticism – turns, like Dadaism, an inside out in order to provide a quite confusing view of human affects in a showroom full of symbols and signs. In this respect, Dadaism was much more clear-cut, pragmatic and thus exoteric in its destruction and in working with set pieces and fragments. Conversely, this leads to the question of whether the disdainful aspect of surrealism lies in a mysticism after all.

Generally, it could be said that signs (by themselves) cannot make any sense because a consciousness is needed to attribute meaningfulness, a cognitive system that attaches meaning to the signs, or like the pragmatist Charles S. Peirce would have said: in order to be a sign, it must be elevated into a Thirdness, into a dimension of interpreting; alongside (1) something that stands for (2) something else. A sensorium is necessary to generate meanings, if they ought to make sense. The sense of symbols and signs can indeed develop in a completely new way within a sensory apparatus, but only if there is the possibility of drawing on a collection of meanings with which an interpretation becomes possible, so to say an anthology of Thirdnesses. These adopted meanings, which also experience a connotative change over time, form the memetic or cultural basis for the interpretability of images, signs and symbols. Therefore, we interpret today’s phenomena with yesterday’s means of interpretation and knowledge and describe ghosts that are generated by consumption, for example, with interpretive and description patterns from a time when thinking was exercised in symbols and less in meanings. Animistic cultures accept the dubious as something that remains unexplained, while things and objects are considered animate, simply because everything is seen as animate. Heidi Holleis’ ghosts could not be new creatures, but certainly some that have been known among other cultures (for example Thai culture) for thousands of years and there could have even been one or the other temple dedicated to them. Maybe this is precisely the reason why there is a Dadaistic snippet from a fashion magazine on the surreal soot; because the contemporary would not make any sense in our sensory apparatus without a projection surface or the background of the outmoded and with this, nonsense would become senselessness and further lead to the assumption that, in fact, only the absence of sense causes fear. In this respect, it is the pragmatic process that helps heaving signs into a Thirdness so that something can make sense.

(Christian Stefaner-Schmid, translated by Maria Magdalena Larch)

1 Mark Fisher, The Weird and the Eerie, London, Repeater Books, 2016, p. 11